- Home

- »

- Germany

- »

- Berlin

- »

- Museum Island

- »

- Pergamon Museum

- »

- The Museum of Islamic Art

- »

- The Pergamon Museum - Mshatta Façade

Mshatta Façade

Mshatta Façade

For centuries, the Bedouins set up their tents at a spot south of Amman, the capital of present-day Jordan. There, a few remaining ruins of ancient walls offered protection against sand storms. The Bedouins called the spot "Mshatta", meaning "winter camp". At the beginning of the 20th century, the tranquility of the place suddenly came to an end. The Hejaz railway was to be built from Amman to the holy city of Medina, and the ruins were in the way. At the last minute, an Austrian scholar realized the incalculable value of what he was looking at.

The walls formed a square, each side was 144 metres. The walls were fortified by 25 towers and enclosed a palace complex that had apparently never been fully built. Only the middle section was layed out, containing living areas, a throne room and a courtyard. But what was truly spectacular were the sections of the outer wall that surrounded the entrance. Flanked by two towers, they were covered in sumptuous reliefs. The scholar decided the facade must be saved.

Wilhelm von Bode in Berlin soon heard of the find. He immediately made contact with the Emperor. William the Second, himself a great lover of art and archaeology, in turn contacted the Ottoman sultan. Abdülhamid the Second resolved the situation without further ado by presenting the entire facade as a gift to his friend William. It was shipped to Berlin in 422 crates and a section measuring 32 metres wide by 5 metres high was erected in the museum.

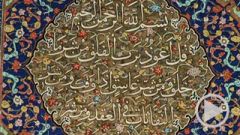

Since then, generations of visitors have immersed themselves in the fairy tale world of the bas-reliefs. A zigzag moulding of acanthus leaves flows across the surfaces of the walls and towers. Rosettes are surrounded by scenes of seeming paradise, done in incredibly rich detail. Never-ending variations of vines grow from the base of the wall or from decorative vessels, climbing with a wild mass of tendrils in circles and spirals up into the points of the triangles formed by the zigzags. Birds are everywhere, pecking at the grapes. And then there are the mythical creatures: griffins, dragons and centaurs. Under some of the rosettes are ornamental fountains, where cattle and lions drink together in harmony. That motif is familiar to us from early Christian-Byzantine tradition – it symbolises heavenly peace.

Of the triangles formed by the moulding, the standing ones are almost completely covered with tendrils. But the hanging triangles present clear evidence that the facade was never finished. It appears that construction was suddenly stopped, although nobody can say for sure why.

Unfortunately, the facade bears no inscription that would help to date it. It's believed that the palace was built by Caliph al-Walid the Second. He assumed rule in 743, but was assassinated just one year later. That may explain why his palace was never finished. Today, only a few fragments of the royal winter palace remain on the grounds of the Amman airport. The facade in Berlin, however, is the greatest and most ornate example of early Islamic architecture.